Forced Arbitration and Work: What You’re Signing Away in the Fine Print

By the National Employment Law Project

What if your employer could short you on overtime pay, steal your wages, or discriminate against you without fear of repercussions?

If you signed a forced arbitration provision when you got your job, they probably can.

More and more, companies are forcing workers and consumers to sign away their right to their day in court, burying forced arbitration clauses in the fine print of the routine forms we sign when we accept a job, open a bank account, or sign with a new cable provider.

Tens of millions of people in the U.S. have signed such clauses in relation to their employment, and the number of people asked to do so in their hiring contracts just keeps climbing. By signing a contract with a forced arbitration clause, you’ve essentially waived your legal right to sue the company in a public court of law over a dispute—no matter how egregious the violation may be.

Say your employer had repeatedly shorted you and several of your coworkers on overtime pay over a period of time—not an uncommon situation. But since you all signed arbitration clauses when you started work for your company, your only option for legal recourse is to enter into private arbitration.

With arbitration, your employer writes the rules, including setting the deadlines and fees. And rather than a jury or an impartial judge hearing your case, the outcome is up to an arbitrator, who was probably hired by the company. Unsurprisingly, studies show that workers win less frequently and receive lower awards when they are forced to go to arbitration, while arbitrators have reported that they feel pressure to rule in favor of the company that hired them.

Though arbitration can be a useful tool for two businesses to use to resolve a dispute efficiently, it operates completely differently in a situation with the kind of fundamental power imbalance that exists between workers and their employers or individual consumers and a major corporation. A core component of the problem is the fact that most of us aren’t in the position to say no to signing a forced arbitration clause when we accept a new job—we need it too badly.

Often, forced arbitration clauses also include “class action bans,” which require you to enter arbitrations individually. An essential tool in our justice system, class actions have long allowed regular people to join together to seek justice from powerful corporations—which is key, since most of us lack the resources to spend thousands of dollars pursuing an individual case, especially over a relatively small amount of money. Without class actions, companies can steal from their employees and consumers, over and over again and virtually free of consequences.

Needless to say, the cards are stacked against you in this environment. And if you do lose in an arbitration hearing, you probably won’t be able to appeal the decision. Worse, you may even have to pay the companies’ lawyers (in addition to your own), for the “hardship” you caused them—which could leave you hundreds of thousands of dollars in debt.

When that kind of outcome is possible, would you roll the dice in an arbitration hearing? Far too often, the nature of forced arbitration prevents workers and consumers from seeking justice at all, and companies are able to get away with habitually robbing the very people who sustain their businesses.

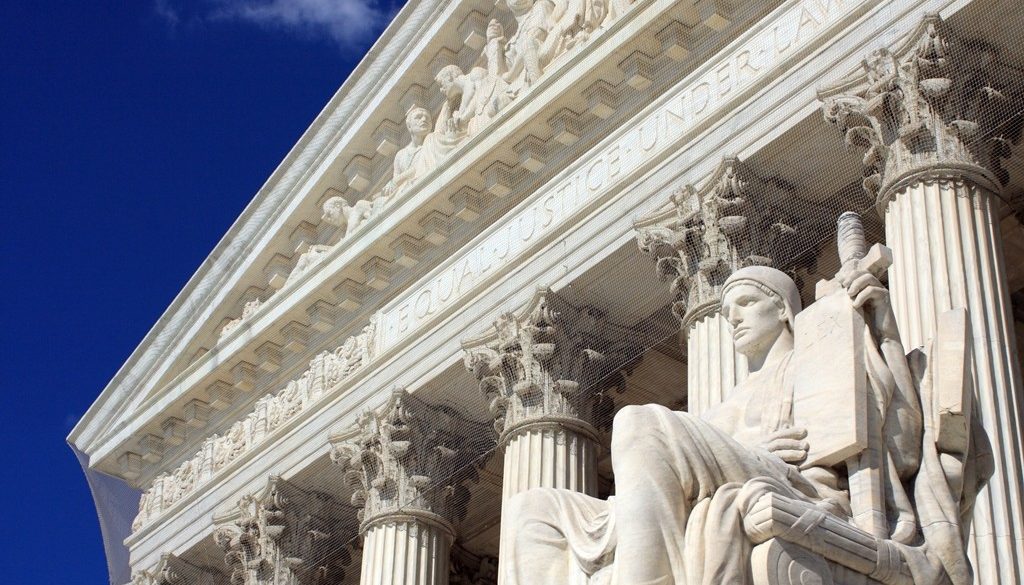

Depending on the outcome, an upcoming Supreme Court case—Epic Systems Corp. v Lewis—could leave ordinary people even more vulnerable to the strangling hand of forced individual arbitration. Among the parties to the case are four employees of a Murphy Oil gas station in Calera, Alabama, who allege that their employer shorted them on overtime and pay for off-the-clock labor—and that their employer’s attempt to make them give up their right to group action and force them into individual arbitration violates U.S. labor law.

If the Murphy Oil employees prevail, it will be much harder for companies to force workers into individual, private arbitration hearings. The Obama administration had filed a brief siding with the workers, but in a stunning and revealing move, the Trump Department of Justice switched sides and filed a brief siding with the companies.

Since the government is a party to the case, this is a disconcerting turn of events for the Murphy Oil employees—and for anyone who thinks that corporations should be held accountable when they break the law at the expense of ordinary people.