EPA Analysis of FracFocus Data Shows We Still Know Far Too Little About Fracking Chemicals

By Matthew McFeeley, Staff Attorney, Land & Wildlife Program, Natural Resources Defense Council

On Friday, the Environmental Protection Agency released a report analyzing data from FracFocus.org. The report provides the most complete look we’ve gotten to date at the chemicals used in fracking fluids and the amount of water used. But most of all, the report highlights how much we still don’t know – because of industry keeping information secret, sloppy reporting, and the fact that disclosure of fracking chemicals and water use is still voluntary in too many states.

Keeping Secrets

In more than 70% of the disclosures[1] to FracFocus during the period EPA studied, one or more chemicals in the fracking fluid were claimed as confidential and not listed. Companies often refused to provide information on many chemicals in the same frack job. On average, five chemicals were claimed to be confidential in the reports where any chemical information was withheld.

The public deserves complete information about the chemicals being trucked into their communities, stored near homes and schools, and injected near groundwater. But unfortunately, even in states where disclosure of chemicals is required, the rules allowing companies to keep information secret are much too weak. The EPA report reminds us that there are still too many unanswered questions about the chemicals being used in communities around the country.

Incomplete and Faulty Data

EPA makes clear in the report that its analysis was limited by error-ridden data. For instance, EPA refused to even calculate average concentrations of chemicals in fracturing fluid because the numbers would be influenced by too many entries they strongly suspected to be errors. And before making other calculations, like total water use, or even the locations of wells, EPA often had to eliminate hundreds or thousands of disclosures with inconsistent or implausible information.

The report looked at just over 39,000 disclosures from 20 states between January 2011 and February 2013. But this is not a comprehensive look at all the fracking occurring during that time. First, there’s evidence that fracking is occurring in 30 or more states, yet fracking from only 20 was only reported to FracFocus. Additionally, no state required reporting to FracFocus until February of 2012 when Texas became the first, more than halfway through the time studied. EPA notes that when Texas’ requirement went into effect, the rate of fracking operations being reported to the site almost doubled, jumping 89%. This indicates that there was a lot of fracking that was never reported to the site before the reporting requirement took effect – and it seems likely that there were many fracking operations going unreported in states without reporting requirements.

EPA was given unprecedented access to the FracFocus data and, unfortunately, more recent data is not available because of limitations FracFocus puts on the public’s ability to download the disclosures. But FracFocus has promised that it will release its full dataset in the coming weeks. NRDC looks forward to FracFocus following through on this important step, and we’ll be taking a close look at the data as soon as it’s released in order to provide more information about how these trends may have changed.

What the data does show is troubling

Fracking uses dangerous chemicals:

Even without knowing about all the chemicals being withheld as confidential, it’s clear from the data that fracking uses dangerous chemicals. For instance, the report found that the three most common chemicals in fracking fluid, each found in about two thirds of the disclosures, are hydrochloric acid, methanol, and hydrotreated light petroleum distillates – all toxic.

Diesel fuel was also reported in fracking fluid 342 times. The use of diesel is a serious concern, as it contains dangerous compounds including benzene, toluene, ethylene, and xylene (referred to as “BTEX” compounds). According to EPA’s Permitting Guidance for fracking using diesel fuels, “BTEX compounds are highly mobile in ground water and are regulated under the [Safe Drinking Water Act] . . . because of the risks they pose to human health.” The EPA has set safety standards for the BTEX chemicals and states that “[p]eople consuming drinking water containing any of these chemicals in excess of the standards set by the EPA over many years could experience:

- An increase in anemia or a decrease in blood platelets from benzene exposure;

- An increased risk of cancer from benzene exposure;

- Problems with the nervous system, kidneys or liver from toluene exposure;

- Problems with the liver or kidneys from ethylbenzene exposure; and

- Damage to the nervous system from exposure to xylene.”

When Congress exempted hydraulic fracturing from the Safe Drinking Water Act, (the exemption often termed the “Halliburton loophole”) it specifically made an exception for fracking using diesel fuel because of its significant health threats. More recently, a panel of experts convened by the Department of Energy recommended that the use of diesel fuel in fracking fluid be eliminated, stating that there was “no technical or economic reason” for its use. Companies have claimed that they’ve phased out the use of diesel, but the evidence has repeatedly suggested that the use of diesel has continued. As more data becomes available, NRDC will continue to track the use of diesel fuel and other toxic chemicals in fracking.

Fracking uses massive amounts of water:

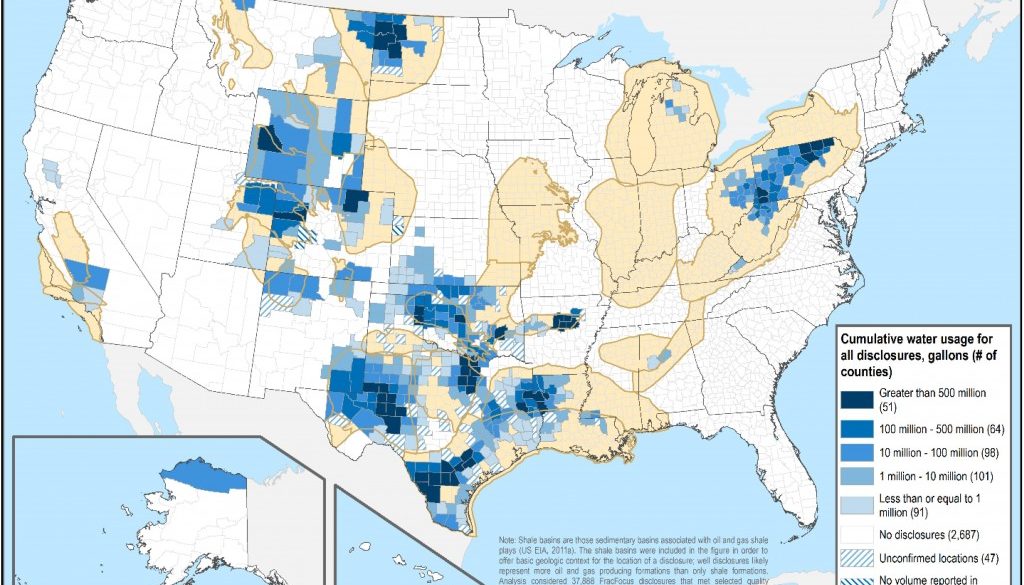

The EPA report found that more than 90 billion gallons of water were used in the fracking operations reported to FracFocus during the period they looked at. This water use can put an enormous strain on communities where water is in scarce supply. For instance, billions of gallons were used in counties which were suffering from drought. Unlike other uses, water used in fracking does not return to the hydrological cycle.

Fracking is happening closer to groundwater sources than industry claims:

The oil and gas industry argues that fracking poses no risk to drinking water because it takes place far below the surface and well below groundwater sources. This argument misses the fact that there are many potential conduits for groundwater contamination, including problems with the well itself or the cement around it that can provide a pathway into groundwater it passes through, faults and fractures in the geology, and nearby wells that are inactive or abandoned and may provide a direct path from deep underground to shallower water sources.

However, fracking very close to groundwater sources is clearly taking place, and is very risky. The California Council on Science and Technology found that “Hydraulic fracturing at shallow depths poses a greater potential risk to water resources because of its proximity to groundwater and the potential for fractures to intersect nearby aquifers.” The data show that fracking is occurring at shallow depths. Despite industry’s assurances that fracking generally takes place at a mile or more below the surface, the EPA found that many fracking operations were conducted at a fraction of this depth – and almost three hundred were done at less than a thousand feet.

[1] A disclosure is a record of a well being fracked – including information on the chemicals and water used, to the extent provided by the company. If fracking was performed on the same well on multiple occasions, this would represent multiple disclosures (assuming that each was reported).