PJM’s Costly Capacity Cushion

By Casey Roberts, Sierra Club

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission’s recent “Minimum Offer Price Rule” order has grabbed headlines for how it will hike electricity costs for 65 million people in the mid-Atlantic region and Ohio Valley to finance a coal and gas bailout. But by forcing consumers to make more costly excess purchases, that order will exacerbate regional transmission organization PJM’s existing problem of capacity overbuying.

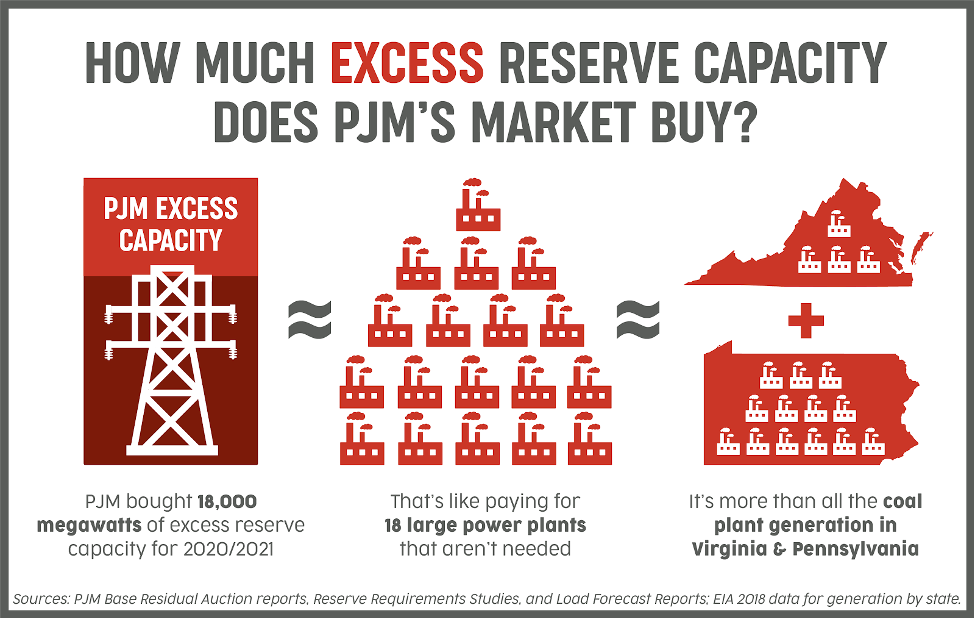

An analysis released this week by Wilson Energy Economics reveals that rather ensuring an extra cushion of electricity generation for any contingency, PJM’s capacity cushion is more like an extravagantly plush feather bed. Year after year, PJM bills consumers for far more excess generation than its own planners say is actually needed. In 2020 and 2021, PJM will charge consumers for about 18,000 megawatts beyond a sufficient buffer. Think of that as approximately 18 additional large power plants — about the current total coal capacity in Virginia and Pennsylvania.

Why the Capacity Market Matters

Before we dig into why PJM procures so much excess capacity, let’s look at why it matters. There are a couple big reasons.

First, excess capacity costs PJM consumers billions of dollars each year. In the new Wilson Energy Economics report, economist James Wilson recreated PJM’s most recent capacity auction but partially corrected two errors that cause over-procurement: overshooting estimates of both future peak demand and the costs of building new generation. The bottom line? Consumers could have saved up to $4.4 billion if PJM had designed its market better.

The other reason we should care about over-procurement is how those excess capacity dollars are being spent. States in PJM’s region are increasingly aiming for a very different energy world than the one we’ve had for the past few decades — with nearly all clean energy sources instead of the pollutants that cost us in health, water cleanup, and a worsening climate crisis. But PJM’s capacity market is steering investment to gas and coal. While coal is being retired in PJM’s region, it’s being replaced by new gas instead of clean energy sources — in contrast to every other region in the country.

According to S&P Global, 29,000 megawatts of new gas are being built or planned in PJM’s region. From 2012 to 2022, nearly 53,000 megawatts of new gas was developed in PJM — three times the amount of renewable energy resources. This trend contrasts sharply with other regional transmission organization markets, where renewables have dominated gas over that same period. Coal also continues to benefit from this glut of capacity. As another recent paper shows, about 18,000 megawatts of coal in PJM would be uneconomical were it not for capacity market payments.

Why Capacity Over-Procurement Is Happening

Now let’s dig into why PJM buys too much capacity. Each year, PJM runs its capacity auction in order to procure commitments from generation owners that they’ll be able to provide a certain amount of electricity three years down the road. PJM draws a demand curve to determine how much capacity it will buy at different price points. This downward sloping curve reflects how much product PJM determines will be needed and what price points will encourage generation owners to build new resources. The prices start off higher to be sure enough capacity is encouraged to meet forecast peak demand plus the target reserve margin (the reliability requirement). Prices then decrease with each additional MW to motivate enough extra cushion (reserve) without generating too much. That’s the theory.

In practice, there are two big issues with how PJM runs the market that end up creating price points that result in too high a clearing price and therefore too much capacity.

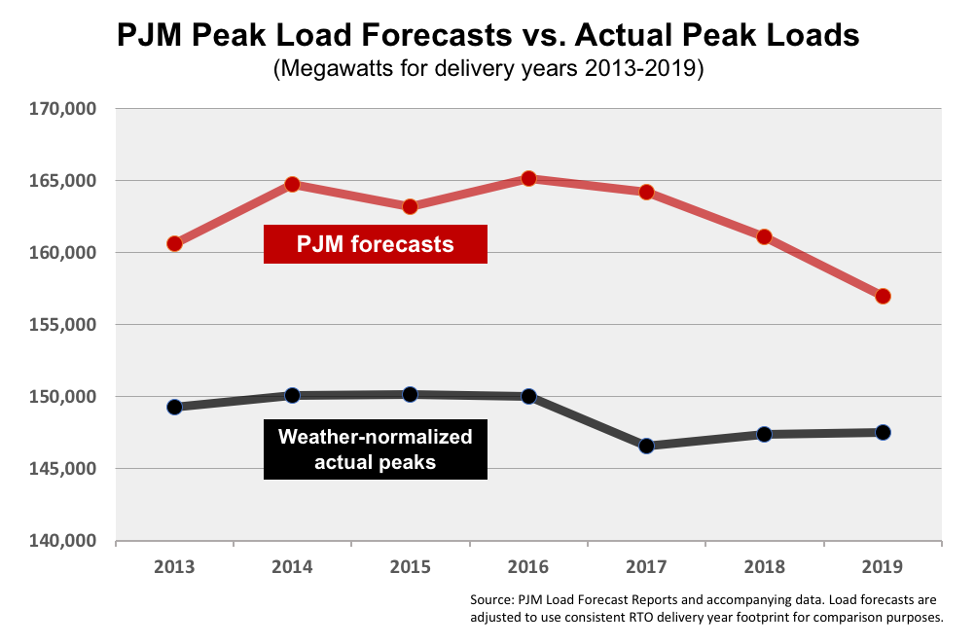

The first problem is that PJM regularly overshoots its estimates of future peak load by about 10,000 MW — this error alone is equivalent to 10-15 unneeded large power plants being built or kept online. This means more higher-cost generation owners fit their higher-cost offers into the market, boosting the eventual clearing price that will dictate how much capacity gets bought. While load forecasts can never be perfect, PJM’s is consistently wrong and excessively conservative. And PJM lacks an effective mechanism to correct for overblown load forecasts as the delivery year draws near, such as allowing consumers to shed unneeded capacity.

The second problem is that PJM overestimates what it actually costs to build generation. So whereas the load forecast problem has to do with how many megawatts PJM encourages through the highest price point in its market, this problem has to do with just how high that price point is. A key input for the demand curve is the net cost of new entry, which represents the amount of revenue needed to make up the difference between the cost of building and operating a combustion gas turbine after taking out what that generator will eventually get paid for the energy it generates.

According to the report from Wilson Energy Economics, PJM consistently estimates costs that are about double the actual prices at which generators are willing to enter the market. In large part this is because PJM assumes the market must support new combustion turbines, whereas combined cycle gas plants account for the overwhelming majority of new entry in PJM’s region. The result? Just as we saw with the overshooting of peak load forecast, these excessive prices create a market that pulls prices higher, accepting more higher-cost offers from more generators and fattening up the extra cushion.

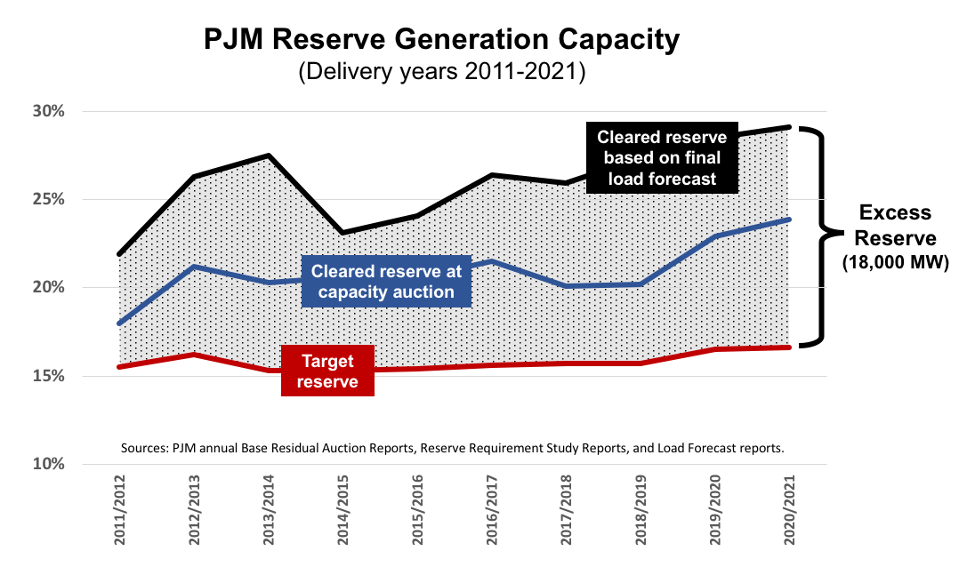

In the graph above, we can see the upshot of PJM’s flawed capacity market designs and errors. While aiming to procure about a 16 percent margin of extra cushion each year (the “target reserve”), PJM’s market has typically ended up clearing a 20 percent or higher margin. And once the final load forecasts come in that show just how much less capacity was actually needed, the total margin of extra cushion ends up north of 25 percent — that plush feather bed.

The analysis by Wilson Energy Economics finds that if the load forecast and excessive net cost of new entry (CONE) issues were even partially corrected, PJM’s capacity market would clear 8,000 fewer megawatts, saving consumers $4.4 billion a year. Full corrections of PJM’s flawed load forecast and net CONE calculation would yield even greater savings.

Everyone wants reliable access to electricity, but consumers are already paying for plenty of it with PJM’s target 16 percent reserve margin. An extra 18,000 MW benefits no one except aging coal and new gas plants. By getting the load forecast right and setting the demand curve based on actual costs of new entry rather than exaggerated ones, PJM would send the right signal for capacity investment in the region. And people could sleep better knowing they’d be saving a lot of money.